Obsession with the marathon

This blog post on the language of the marathon is shamelessly influenced by your blogger’s obsession with running!

April is the month when Londoners and Bostonians turn out in their droves for two of the finest city marathons. And this year I will be attempting to run both, a total of 52.4 miles with just six days in between. Looking for inspiration I delved a little into the etymology and origins of the marathon – this feat of athletic endurance.

Etymology of the marathon

The story goes that in 490 BC the Greek soldier Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens to deliver news of military victory against the Persians, whereupon he collapsed and dropped dead of exhaustion. In honour of his achievement the modern distance running event takes its name from the site of the military battle: “Marathon”, which is itself derived from the Greek word for “fennel” which grew in abundance in the fields around.

No doubt there is a fair bit of artistic licence in this original marathon legend, but what is true is that the Greek army in those days used so-called hemerodromoi or ‘all-day running couriers’ to ferry messages back and forth. Some suggest that Pheidippides’ name itself means “to spare the horse” (from pheido “thrift” and hippos “horse”) – a reference to the fact that runners could outperform horses on this tricky terrain. It is also possible that Pheidippides may, in fact, have achieved a far greater feat than a mere 25 mile trot from Marathon to Athens. Fifth century historian Herodotus reports that, prior to the Battle of Marathon, Pheidippides was sent to Sparta to ask for assistance. He is said to have completed the run of around 153 miles in two days before running back to Marathon bringing mixed news. Yes the Spartans would help, but not for another 6 days as superstition meant they had to wait for a full moon before going into battle!

We have a linguist to thank for the invention of the modern marathon. French philologist Michel Bréal (often regarded as the founder of modern semantics) was a friend of Pierre de Coubertin who instigated the nineteenth century revival of the Olympic Games. Bréal was perhaps inspired by Robert Browning’s poem and its romanticised retelling of the Pheidippides story:

He flung down his shield

Ran like fire once more: and the space ‘twixt the fennel-field

And Athens was stubble again

At any rate, Bréal suggested the inclusion of a 25 mile running event in the programme for the first modern Olympics in 1896. The race would be named in French “marathon” after the Greek “Μαραθών”.

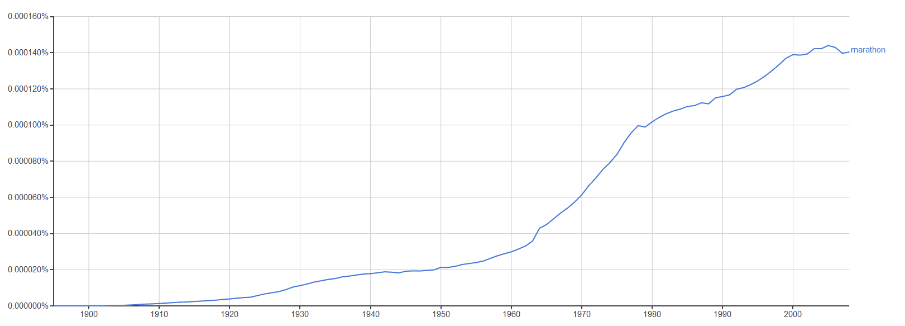

Language of the marathon: Google Ngram

Language usage also reveals something about the history of this event. Just take a look at Google’s Ngram graph plotting usage of the word “marathon” between the late 19th century and today. A steady increase in use can be seen from the first Olympic marathon up to the 1960s at which point the trajectory tilts steeply upwards through the running boom of the 1970s and 80s before plateauing out somewhat at the millennium.

If this analysis of the language of the marathon suggests that marathon running may have reached its peak – what could be next? Well, some say that hard-core runners have already moved on, setting their sights in increasing numbers on the “ultramarathon”: any race which is longer than 26.2 miles in length. And, some would argue, rather closer in definition to Pheidippides’ original undertaking. Indeed the modern day “Spartathlon” is a 153 mile race held between Athens and Sparta in his honour. I’m not sure whether that’s inspiring or horrifying.

Rosetta Translation is a full-service translation agency in London, specialising in contract translation, court interpreting and Chinese translation.

About the Author

Alison Tunley

Alison is a seasoned freelance translator with over 15 years of experience, specialising in translating from German to English. Originally from Wales, she has been a Londoner for some time, and she holds a PhD in Phonetics and an MPhil in Linguistics from the University of Cambridge, where she also completed her First Class BA degree in German and Spanish… Read Full Bio